Oratio transliterates as “prayer”, but obviously our word “prayer” is a catch all. Lectio and Meditatio and Contemplatio are also forms of prayer.

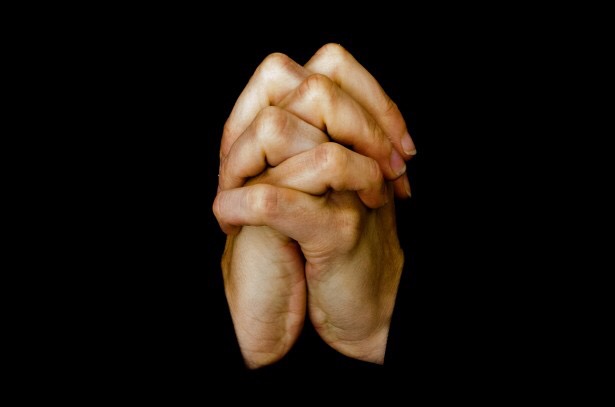

Oratio is more specifically the heart’s reaching out to God. The heart is the seat of the will. This is where we choose God or ourselves. Where we choose good or evil.

If in lectio we engage with the senses (touching the page, reading the text), and in meditatio we engage with the intellect (asking questions, imagining the scene), in oratio we engage with the will.

Oratio is often called “mental prayer,” but that’s misleading because we’re not talking about thinking at this point. That’s meditatio. I think the best modern translation of oratio is “interior prayer.”

This is where we enter into conversation with our Lord. St Teresa of Avila puts it this way:

“Oratio in my opinion is nothing else than a close sharing between friends; it means taking time frequently to be alone with him who we know loves us.”

Teresa of Avila, The Book of Her Life, 8,5.

It means applying what we have read and thought and imagined to our present and our future. We might share some thought, or ask for a grace or favour, or make a resolution to act or think some way. (This is naturally what happens, when we’re in the company of anyone we love.)

Because our normal interactions with people we love are incarnate, but in the Lord’s case we’re dealing with someone who is invisible to our senses, I think oratio is the hardest type of prayer. Harder than lectio and meditatio, anyway. But like going to the gym, it gets easier with practice. The senses can be trained to permit the interior silence which facilitates focus on the Lord.

“You will only have to make a sign to show that you wish to enter into recollection and the senses will obey and let themselves be recollected.”

Teresa of Avila, The Way of Perfection, ch. 28.

Still, Teresa is adamant that oratio is something we will, not something mystical.

“You must understand that this is not a supernatural state, but depends on our will, and that, by God’s favor, we can enter it of our own accord. . . . For this is not a silence of the faculties; it is an enclosing of the faculties within itself by the soul.”

Teresa of Avila, The Way of Perfection, ch. 29.

Don’t find time, make time

That means that we should schedule oratio into the day. It also means that if we scheduled ten minutes, we don’t abandon ship at seven minutes. We have to persevere! My old seminary confrere and well-known priest, Fr Rob Galea, has a good rule. He schedules a very precise 31 minutes of prayer to eliminate the temptation, during a hard slog, to round up 26 or 27 minutes to “half an hour.”

Find somewhere quiet

Ideally, we sit before the tabernacle. But remember, “pray as you can, not as you ought.” Oratio can be done at home — before an icon or holy image. It can be done in the bush or on a mountain top. As long as the place is quiet and lends itself to conversation with God.

Get comfortable

If you prefer sitting to kneeling, then sit. If an extreme temperature distracts you, then turn on the heater or air conditioning. Oratio is not the time to mortify the senses. Remember, we need to train ourselves to quieten the senses, so that we can focus our will on God.

Now I can do all this — schedule time, find somewhere quiet, get comfortable — and then conduct a monologue. It’s very easy to think about myself, imagine conversations with other people, and plan my next meal. Hardly a raising up of my heart to God. So St Teresa gives one more word of advice:

BRING A BOOK!

The fuel for oratio, and the greatest protection against monologue, are the previous steps I blogged on: lectio and meditatio.

As Saint Augustine puts it:

“Your prayer is the word you speak to God. When you read the Bible, God speaks to you; when you pray, you speak to God.”

Augustine, Enarrationes in Psalmos, 85, 7: PL 37, 1086.

Recent Comments