We’ve all had uncomfortable conversations which we’d rather avoid. In those moments it’s tempting to misrepresent one’s true thoughts and keep the peace.

Priests have lots of these conversations, though possibly no more than others. But priests have a big advantage. Priests minister sacramental confession.

When I am hearing confessions, I’m acutely conscious that I act in persona Christi. It is one of those very rare moments when I am enabled and obliged to judge another person. I certainly don’t do this on my own behalf, but only in service to the Lord, whose justice and mercy I minister.

No one on earth will ever know the advice I give to penitents. But God knows. This is one instance when the easy way out — acquiescence and agreeability — is not an option at all. Since I speak for God, not for myself, I am absolutely obliged to be faithful to God’s truth.

At the same time, the penitent is in a very vulnerable position. (I know, because I’m frequently a penitent myself!) They have just opened up their heart, and exposed their inner life. Not to me, but to our Lord. So I have another obligation, no less grave: to be kind. To minister the Lord’s mercy.

I do not remember the sins I hear in the confessional, because I ask to forget them, and the Holy Spirit grants me that favour. But though I remember nothing, the act of hearing confessions changes me. I am practiced in speaking the truth with love, which is often a very challenging task.

But of course this task, the duty to proclaim the truth with love, is not exclusive to priests. Every Christian is called to do this. Even in the most awkward conversations, the most unwanted confrontations, we must be faithful to truth, and faithful to charity.

I think veritas in caritate has a certain “look.” It is serene. It is good-humoured. And it is humble. But it is seldom easy.

An impressive account of veritas in caritate appeared in my Facebook newsfeed today. It was a shining beacon in the midst of an ever-rolling stream of ill-measured and inflammatory comments.

The other day we got together with a friend of mine from high school named Andrew, and his boyfriend, Tom. We caught up on life and work, Andrew and I clicking as well as we always have. I wore waterproof mascara because I knew I’d end up laughing to the point of tears, which, in fact, I did.

Then, when my husband and Tom went to pick up a round of drinks at the bar, Andrew had a question for me. “So,” he said, grabbing a tortilla chip from the basket in front of us. “What do you think of gay marriage?”

The last time we hung out, this unspoken topic was not as palpably present as it was now. Even though our gay friends knew that we’d converted to Catholicism, nobody cared enough to bring up potentially controversial issues. But now, the mood in the world around us had changed. Throughout our country the issue of same-sex unions was being debated furiously; it had become a defining issue of our generation, and thus the average person was no longer allowed not to have an opinion about it. It was too weird to sit at the table, two orthodox Catholics and two men in a gay relationship, and not bring it up. We could no longer ignore the storm that raged outside the cloister of our friendship; the doors had blown open, and the rain had come inside.

I shrugged, trying to keep it casual.

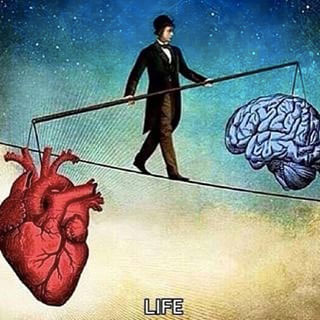

This is one of those awkward conversations we’d all rather avoid. But the author, Jennifer Fulwiller, doesn’t do this. Instead she attempts that elusive balancing act of truth and love.

Read it all. It’s worth it.

Very interesting and touching story from Jennifer.

I believe persons who are afflicted with same sex attraction are particularly beloved of the Lord because their Cross is heavy, it brings them closer to Him Who also embraced celibacy and chastity and will give them the grace to show the world you can live, love and be happy without sexual activity.

I believe that homosexuals who struggle to stay chaste will experience Christ’s love more deeply than those of us straights who are also bound to be celibate.

We straights must make a particular effort to give our affection, respect and warm friendship to homosexually-oriented persons. They need very good friends.