Today is the feast of St Anna the Prophetess. Everything we know about Anna derives from a few verses in Sacred Scripture (Luke 2:36-38):

- Anna was a prophetess. Her name means “grace.”

- She was the daughter of Phanuel. This name derives from מְּנוּאֵל, meaning “the face of God” (Gen 32:30).

- She was from the tribe of Aser, one of the ten lost tribes of Israel.

- She was very old — at least 84 years old. Many scholars, from St Jerome to Raymond E. Brown, believe that she was widowed for 84 years, which made her 104 or 106 when she encounters the Holy Family.

- She was married for 7 years before she was widowed.

- She spent all her time at the Temple.

- She prayed and fasted devoutly.

I want to hone in on St Anna’s fasting, which is a noble spiritual practice. Our Lord fasted too of course, as has everyone who has cultivated the spiritual life, before Christ and after Christ, in the Christian Tradition and outside it.

St Anna models very well for us the positive fruits of fasting:

Long life

If Anna really was 106 years old — or even if she was 84 — in first-century Jerusalem she’s very old!! The science is far from settled, but a growing body of research suggests that people who fast live longer. This research was perhaps most famously popularised by Michael Mosley’s Eat, Fast, Live Longer BBC documentary. When it was broadcast in 2012, it generated a new intermittent fasting craze in the United Kingdom. I don’t recommend fad diets, but I do recommend the documentary, viewable on Daily Motion.

Perhaps Anna’s long established habit of fasting contributed to her longevity.

Peace and Charity

Our Lady and St Joseph had just met Simeon when they encountered Anna. We can imagine how Simeon’s prophecy must have distressed them:

“You see this child? He is destined for the fall and the rising of many in Israel. Destined to be a sign that is rejected — and a sword will pierce your own soul too — so that the secret thoughts of many may be laid bare.” (Lk 2:34-35)

This is a very insensitive thing to say to a young mother! I think we can agree on that without criticising Simeon, who is a good and holy man, favoured by God, who is speaking the truth with only the best intentions. Simeon’s prophecy is important. It needed to be said. But still, it would have hurt.

Cue Anna, whose exacts words St Luke does not record. Still, it’s easy to imagine that Anna spoke words of compassion and reassurance which soothed the young Galileans, because let’s face it: that’s our experience too, isn’t it? Godly old women do peace and charity really well.

I’d argue that Anna’s long established habit of fasting also contributed to this talent. It enabled her not only to recognise Mary’s immediate needs; it also enabled her to distinguish the young Galileans from the thousands and thousands of pilgrims she’d observed over many decades. Anna’s long established habit of fasting enabled her to correspond with God’s grace, and recognise when she was gazing at the face of God.

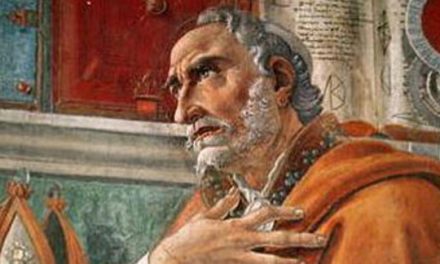

The Prophetess Anna, Rembrandt, 1631.

Good fasting fosters inner peace

Good fasting — the sort which St Anna observed, and our Lord, and all his saints — harmonises body, mind and spirit. (Fasting by the way, is not limited to food. We can discipline any of our sensual appetites by limiting food, or alcohol, or TV, or Internet, or sleep, etc. etc.)

In contrast, bad fasting is an act of violence which sooner or later causes a violent reaction — often binge eating, or recourse to some other sensual consolation. Bad fasting often exacerbates compulsive behaviours and addictive patterns. “We steal in the dark what we do not receive in the light!” Bad fasting is not sustainable.

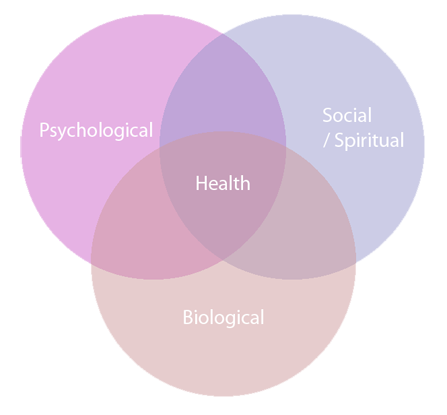

Good fasting, in contrast, is perfectly sustainable. Remember, it is a means to inner peace. The bio-psycho social-spiritual model of health helps us see this:

Fasting disciplines the physical appetites, so that our biological needs are harmonised with our psychological, social, and spiritual. Harmony fosters holistic health — that is: physical-mental-social-spiritual wellbeing.

Sometimes the body is viewed as an enemy to the spiritual life, and fasting is framed as a weapon by which we tame the beast or chasten the traitor. That’s the view that informs bad fasting: an act of violence — or at last an act of domination. Mind over matter. Will over appetite. But as well as risking a violent sensual reaction, this outlook can lead to semi-pelagianism: over-reliance on personal will, to the detriment of divine grace.

St John Cassian gives us a good example of this in his treatment of monastic fasting. For the desert hermits, he counsels two loaves of bread every day. No more, no less. And he warns against bad fasting:

You know that your fellow citizen Benjamin most obstinately stuck to this: he would not every day partake of his two loaves with uniform self-discipline, but preferred to continue total fasts for two days. Then, when he came to eat, he could fill his greedy stomach with a double portion, and by eating four loaves enjoy a comfortable sense of repletion. He managed to fill his belly by means of a two days’ fast.

The ill-fated Benjamin did not persevere in the monastic vocation. Excessive self-denial leads to an inevitable biological reaction, by which the appetites assert their dominance over the will.

The Church’s answer, as always, lies in the virtues — habitual goodness, borne by love of God. The virtuous person has harmonised their appetites. Their desires are integrated, not suppressed. The sacred and profane are united in common purpose. (Our Lord, in particular, exemplifies this.)

Good fasting is especially governed by prudence or practical wisdom: doing the right thing, at the right time, for the right reason. Cassian refers to discretion, which is the same thing. An example of practical wisdom is shown in his solution to the dilemma of balancing self-denial with hospitality:

Both duties must be observed in the same way and with equal care. We most scrupulously preserve the proper allowance of food for abstinence’s sake, while also out of charity showing courtesy and encouragement to any brethren who may arrive. It is absolutely ridiculous to offer food to a brother — nay, to Christ Himself — but not partake with him, instead making oneself a stranger.

We shall be clear of guilt on either hand if we observe the following plan: at 3pm eat one of the two loaves which form our proper canonical allowance, and keep back the other until evening, just in case of the unexpected guest. Should any of the brethren comes to see us we may break bread with him, adding nothing to our customary allowance. By this arrangement, the arrival of our brother — which ought to be a pleasure — causes no inconvenience, since we can reconcile self-denial and charity.

What’s the take home lesson? Fasting is good for us — really good for us — when it harmonises the physical, mental, social and spiritual. But navigating that requires a lot of wisdom. The sort of wisdom which might be expected of a 106-year-old prophetess, but which may not come so easily to you and me. This is why we need community, and maybe even a spiritual director. For in the words of St Bernard of Clairvaux:

“Anyone who takes himself for his own spiritual director is the disciple of a fool.”

Recent Comments